The Commerce Clause

Everything's Coming Up Commerce: The Musical!

Enjoy this splashy Broadway style review that takes you through the history of the commerce clause. The most fabulous experience in Constitutionland is all about the most fabulous clause in the U.S. Constitution. This lavish Broadway (style) musical sings and dances its way from the early days of the Confederation government to the 21st century. With catchy tunes, beautiful showgirls and compelling characters, you will never look at the Commerce Clause in the same (non-musical) way again! Meet James Madison, John Marshall, Thomas Gibbons, Aaron Ogden, the Schechter brothers, Justice Sutherland, Roscoe Filburn and Diane Monson in this American Operetta that attempts to answer the age-old question...what is commerce?

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, 1787: “The Congress shall have power…To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.”

Commerce Clause Origins and Background

The Birth of the Commerce Clause: The Annapolis Convention

The significance of the Commerce Clause in the Constitution cannot be overstated. It is fair to say the Constitution itself owes its existence to regulating commerce. The Articles of Confederation, the immediate predecessor to the U.S. Constitution, was the official governing document of the U.S. from March 1781, until it was replaced by the Constitution in 1789. A noble but flawed attempt to unify the states, it required 9 of 13 states to accomplish anything and unanimity for amendments. The only option the national government had to raise revenue was to pass a tri-cornered hat around to the states and ask them to throw in a couple of bucks… something the states rarely did. Perhaps one of the greatest flaws of the Articles was its inability to resolve conflicts among the states, particularly in the area of commerce.

The Annapolis Convention, as it has been christened by history, was a meeting of twelve "commissioners" from five states called by the Virginia Assembly to "take into consideration the trade and Commerce of the United States" and to propose a "uniform system in their commercial regulations."

With only five states in attendance, the Commissioners mandated that a "future convention" be convened for the purpose of addressing "other objects, than those of commerce." Clearly, it was not simply the poor attendance that encouraged convening a subsequent convention. As the Report of the Annapolis Convention concluded: "the defects [with the Confederation], upon a closer examination, may be found greater and more numerous, than even these acts imply." Hence the Convention adjourned, calling for a future meeting of a "Convention of Delegates from the United States, for the special and sole purpose of entering into this investigation, and digesting a plan for supplying such defects as may be discovered to exist." The meeting was to take place "at Philadelphia on the second Monday in May next." That meeting became the Philadelphia Convention, the most significant gathering in constitutional history. And, it all began for the purpose of regulating commerce. Visit the Annapolis Convention in Predecessors Park for more.

From Proceedings of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government: 1786 Note for September 14, 1786. The Avalone Project http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/annapoli.asp

Also see Clinton Rossiter, 1787 The Grand Convention (1966) pp 48-57 and Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009) pp. 18-21.

Debating the Commerce Clause at the Federal Convention

While the delegates to the Philadelphia Convention disagreed on a number of issues, they seemed uniform in their belief that the government must have the power to regulate commerce. According to Madison’s Notes from the Convention, Roger Sherman, speaking on June 6, 1787, identified as one of the “few objects of the union…regulating foreign commerce.” On June 15, also according to Madison’s Notes, William Patterson presented what became known as the New Jersey Plan which proposed merely to amend the Articles of Confederation. One of the amendments would give the Congress the power: “to pass Acts for the regulation of trade & commerce as well with foreign nations as with each other.”

The debate on regulating commerce dealt with the new federal government’s ability to tax, limit or ban the importation of slaves—a topic raised on August 22 and tabled in hopes of finding a middle ground. Various delegates made it clear the way these issues were resolved could kill the entire convention. Ultimately, the compromise that was acceptable to all allowed a ban on importation of slaves to take effect in 1808 (thus guaranteeing importation until that year). An additional debate took place on the 22nd of August and again on the 29th over a proposal requiring a two-thirds vote in the House and Senate for the purpose of passing navigation acts. The proposal did not pass.

From Notes on Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison. The Avalone Project. June 6, 1787 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_606.asp). June 15,1 787 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_615.asp). August 22, 1787 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_822.asp). August 29, 1787 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_822.asp).

Commerce was debated on September 4, 1787, as reported by Dr. James McHenry, a delegate from Maryland (and the namesake for Fort McHenry…of Star Spangled Banner fame…in Baltimore Harbor). McHenry’s Notes reveal on that date, while the delegates were reviewing the draft of the Constitution, he noted “the national legislature” was not given the power to “erect light houses or clean out or preserve the navigation of harbors.” The proposal was that the expense of these items should “be borne by commerce.” Later on September 6, the convention discussed “enabling the legislature to erect piers for protection of shipping in winter and to preserve the navigation of harbours.” Gouverneur Morris expressed his belief that the power was implied. Eventually, those powers were exercised by Congress under the Commerce Clause (see below).

McHenry’s Notes, in the following quote, also allude to a power eventually called the Dormant Commerce Clause which prevents the states from regulating interstate commerce, since that power is one possessed by the federal government:

“Is it proper to declare all the navigable waters or rivers and within the U. S. common high ways? Perhaps a power to restrain any State from demanding tribute from citizens of another State in such cases is comprehended in the power to regulate trade between State and State.”

No action was taken in the convention on any of these proposals.

From Papers of Dr. James McHenry on the Federal Convention of 1787. The Avalone Project. (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/mchenry.asp).

On September 15, as the delegates neared the final draft of the Constitution and as the convention was winding down, Dr. James McHenry and Mr. Daniel Carroll raised the question of whether states could charge duties of tonnage--taxes on ships in states' ports based on their weight. (Appropriately, delegates from Maryland, with Baltimore harbor and a strong shipping industry, asked the question.) Their concern was over the ability of states to raise revenues in order to afford improving harbors and building lighthouses. This was the flip side of the approach authorizing the federal government to build lighthouses. His thought was if the federal government didn't build them, the states would be left with the obligation of building and maintaining lighthouses and would need a way to pay for them. They ultimately settled upon the language: "No state without the consent of Congress shall lay a duty of tonnage."

From Notes on Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison. The Avalone Project. September 15, 1787 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_915.asp).

James Madison on the Commerce Clause: Federalist No. 42

Madison explains in Federalist No. 42 a principal reason behind empowering the federal government to regulate interstate commerce. “A very material object of this power was the relief of the States which import and export through other States, from the improper contributions levied on them by the latter. Were these at liberty to regulate the trade between State and State, it must be foreseen that ways would be found out, to load the articles of import and export, during the passage through their jurisdiction, with duties which would fall on the makers of the latter, and the consumers of the former.” To explain this in simple terms, in the event a state such as Pennsylvania were to have its goods travel through New Jersey on their way to New York, the exclusive power to tax imports and exports in the federal government would prevent New Jersey from levying a tax on that trade.

Madison was discussing something which became known as the dormant commerce clause (or negative commerce clause) which holds that the states cannot regulate commerce because it is a power held by the federal government to the exclusion of the states. Madison cites as examples in other countries the Cantons in Switzerland and German Princes; neither charges tolls or duties on the goods of other Cantons or German territories when they travel over their territories.

From The Federalist Papers: No. 42. January 22, 1788. The Avalone Project. (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed42.asp)

Lighthouses and the Commerce Clause

One of the first acts passed by the first federal congress was the Lighthouse Act of 1789, whereby States could either build and maintain their own lighthouses, or turn over existing lighthouses (and deed over the land on which they were built) and give power for future lighthouse construction to the federal government for them to run and control...and foot the bill.

Professor Adam Grace’s law review article--a thorough treatment of the Lighthouse Act--raised the interesting point that prior to and during the ratification process, the states constructed and maintained lighthouses effectively. What occurred to change their construction, operation and control from the states to the federal government? And why did it happen in the early days of the new government? From his research, he concludes the reason the federal government assumed responsibility over lighthouse construction and operation was “not important as a national public works policy, but as a taxation policy.” The Congress wanted to have the power to lay duties of tonnage in order to raise revenue. However, by denying states that revenue, states would not be able to raise money for lighthouses. If the states continued to bear the cost of lighthouses, rightfully, they would seek the approval of Congress, as mentioned above, to charge duties of tonnage to defray the costs. That would lead to widely disparate tonnage rates (depending on the state port and the number of lighthouses in each state) and a similar lack of cohesion reminiscent of the Confederation days. Thus, this desire of uniformity led to the Lighthouse Act of 1789. Interestingly, that act became a great legislative precedent for federal control of commerce, and the first federal assertion of the commerce clause, predating Gibbons v. Ogden by 36 years.

In debates over the Lighthouse Act of 1789, the federal government’s power under the commerce clause to construct and maintain lighthouses was addressed:

“In 1789, when the First Federal Congress first sat, it would not have been clear to everyone that (1) the federal government had the power to construct lighthouses; and (2) the power to "regulate" commerce included the power to "facilitate" commerce by constructing such internal improvements. Nevertheless, the Commerce Clause precedent created by the Lighthouse Act remained virtually unquestioned, even while the power to "construct" improvements and "facilitate" commerce would be debated for decades in relation to proposed road and canal programs. Whether the lighthouse precedent was to be accorded broader application was heavily debated, but the precedent of federal lighthouse building was never overruled.”

Adam S. Grace, From The Lighthouses: How the First Federal Internal Improvement Projects Created Precedent that Broadened the Commerce Clause, Shrunk the Takings Clause, and Affected Early Nineteenth Century Constitutional Debate, 68 Albany Law Review 97 (2004)

Commerce Clause in the Supreme Court: 1824 to 1918

Gibbons v. Ogden: Commerce Clause Power Established

2 U.S. 1 (1824)

QUICK SUMMARY: Chief Justice John Marshall breathes life into the Commerce Clause, empowering the federal government to regulate anything and everything traded or that travels in the commerce between the states.

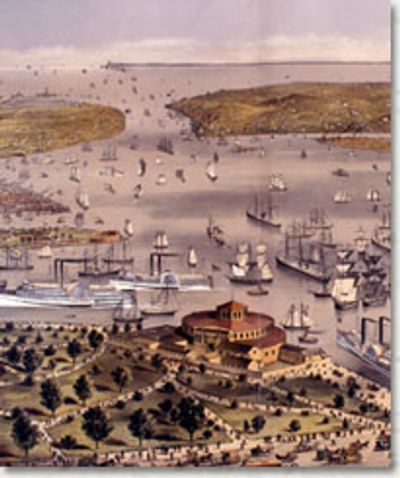

THE FACTS: One of the most famous Supreme Court decision, and one of Marshall’s great opinions, resolved this Constitutional clash between Aaron Ogden and Thomas Gibbons. Aaron Ogden operated a steamboat ferry service over the Hudson River, under an exclusive license from the state of New York. Thomas Gibbons operated a competing steamboat ferry service under a license from the federal government. When Ogden sought and won an injunction in the New York courts barring Gibbons from operating his ferry service, this case found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

THE DECISION: For the first time in the Supreme Court’s history, Chief Justice John Marshall expounds upon the Commerce Clause, with a classic Marshallian flourish. Marshall made the following conclusions:

What is “Commerce?” More than simply “trade,” commerce includes “all commercial intercourse between nations.”

What is the meaning of “among the several states?” Any “commerce which concerns more States than one.”

What does it mean to “regulate?” To “prescribe rules by which commerce is governed.”

Can a State regulate Commerce among the states while Congress is regulating it? Under the Supremacy Clause an act of Congress is supreme to a state law. Although a state may act properly in passing a law, if it conflicts with a federal law, the state law must “yield” to the federal law.

Is there any limit to Congress’ power to regulate Commerce? Any limitations to this power exist in the people’s power at the ballot box to vote out a Congress that over reaches.

What about the “purely internal affairs” of a state? States have the exclusive power to regulate commerce that begins and ends wholly within a state.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: One of John Marshall’s Triumvirate of cases (along with Marbury and McCullough) expanding the powers of the federal government. Gibbons sets the stage for a broad interpretation of the Commerce Clause...and empowers the Congress and federal government to act boldly in the future. For more, visit the Gibbons v. Ogden Steamboat Races in Big Cases

All quotes are from Gibbons v. Ogden 2 U.S. 1 (1824).

Cooley v. Board of Wardens: The Concurrent Commerce Clause

53 U.S. 299 (1852)

QUICK SUMMARY: The Court holds the mere existence of the Commerce Clause does not bar states from regulating commerce over subjects that do not require uniformity of regulation.

THE FACTS: Pennsylvania enacted a statute that required all vessels entering or leaving the port of Philadelphia to hire a local pilot or pay a fine (“one half the regular amount of pilotage”) to the master warden of the port with proceeds to go to “the Society for the Relief of Distressed and Decayed Pilots, their widows and children.” Cooley, the owner of the ship “Counsel” which sailed from Philadelphia, refused to hire a pilot and was fined. He challenged the law as an unconstitutional infringement on the Commerce Clause.

CONCURRENT FEDERAL AND STATE POWERS TO REGULATE COMMERCE: Justice Benjamin R. Curtis concludes what is settled law since Gibbons, that the “power to regulate commerce includes the regulation of navigation.” Additionally, Curtis identifies “pilot laws” as regulation of navigation and, therefore, under the Congress' Commerce Clause power. However, simply because Congress has that power, does not preempt the states from acting: nothing in the Constitution “expressly exclude[s] the states from exercising an authority over [a] subject matter.” Curtis contrasts grants of exclusive power to Congress “like that to legislate for the District of Columbia” with powers concurrent in the federal and state governments, such as “the power of taxation.” He concludes the “mere existence” of congressional powers does not preclude the states from legislating.

THE SUBJECT OF REGULATION AND NEED FOR UNIFORMITY: What determines whether federal power to regulate commerce precludes the same power in the states? The court must examine what is being regulated—sometimes the “subject” of a regulation is of “such a nature as to require exclusive legislation by Congress.” That occurs when the subject or category of regulation “demand[s] a single uniform rule operating equally on the commerce of the United States.” So, when a multiplicity of rules among the numerous state jurisdictions will be an obstacle to commerce among the states, uniformity is required, and the subject of that commerce demands a single federal rules and precludes separate state regulations.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: The debate over how much power the states have to regulate commerce was one that continues to this day. The different extremes included Daniel Webster’s approach, and argument in Gibbons that the federal government had “complete exclusive” power under the commerce clause, to Chief Justice Roger Taney’s concurrent power theory, arguing the states posses full power to regulate commerce absent conflicting federal law. Chief Justice John Marshall allowed for state power over commerce “provided [the states] do not come into collision with the powers of the general government, [and] are undoubtedly within those [powers] which are reserved to the states.” The concurrent powers argument of William Wirt, who was co-counsel with Webster in Gibbons, carried the day with Justice Curtis. Justice Samuel L. Miller in a subsequent opinion commented on the Cooley decision: “Perhaps no more satisfactory solution has ever been given of this vexed question than the one furnished [in Cooley].” According to Bernard Schwartz in A History of the Supreme Court, “Over a century later, much the same comment can be made…the court has basically continued to follow the Cooley approach in cases involving the validity of state regulations of commerce.”

All quotes are from Cooley v. Board of Wardens 53 U.S. 299 (1852). Additional quote Bernard Schwartz, A History of the Supreme Court, pp. 86-87 (1993).

US v. E.C. Knight: The Commerce Clause and the Industrial Revolution

156 U.S. 1 (1895)

QUICK SUMMARY: The Fuller Court declares unconstitutional progressive era legislation regulating the manufacture of sugar; the Supreme Court holds the commerce clause does not permit the federal government to regulate purely local matters, which are under the control of the states under their police power.

THE SHERMAN ANTI-TRUST ACT: At the end of the 19th century, with the Industrial Revolution in full swing, the Congress began passing laws in response to the terrible treatment of America’s poor and working class. An important corollary of this movement involved regulating the monopolistic tendencies of giant corporations. In 1890, the U.S. Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act which declared illegal “every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among several States.”

THE FACTS: In 1892 the American Sugar Refining Company acquired all of the stock of its leading competitors, one of which was called the E.C. Knight Company, and control over nearly one hundred percent of the sugar refining business in America. The federal government filed suit to reverse the sale, under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. This was the Supreme Court’s first review of the constitutionality of the Act.

STATE’S POLICE POWER vs. FEDERAL COMMERCE CLAUSE POWER: Chief Justice Fuller acknowledges the power of the federal government under the Commerce Clause but states that it is subject to the police power of the states. He defines the police power as “the power of a State to protect the lives, health, and property of its citizens, and to preserve good order and the public morals.” This power is exclusively in the states and “not surrendered by them to the general government nor directly restrained by the Constitution of the United States.” The issue is to determine whether something falls under the Commerce Clause or this police power: “That which belongs to commerce is within the jurisdiction of the United States, but that which does not belong to commerce is within the jurisdiction of the police power of the State.”

INDIRECT AFFECT: Case establishes a distinction…Congress cannot regulate something, like manufacturing, that has only an indirect affect on interstate commerce: “Doubtless the power to control the manufacture of a given thing involves in a certain sense the control of its disposition, but this is a secondary, and not the primary, sense, and although the exercise of that power may result in bringing the operation of commerce into play, it does not control it, and affects it only incidentally and indirectly.”

MANUFACTURING IS NOT COMMERCE: The court defines manufacture: “[m]anufacture is transformation -- the fashioning of raw materials into a change of form for use.” With regards to that process the court establishes the general rule: “Commerce succeeds to manufacture, and is not a part of it.” In sum, just because goods ultimately find their way into interstate commerce does not mean the Congress can regulate the manufacture of said goods.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: Chief Justice Fuller insulates the manufacture of a good from congressional control under the commerce clause because if manufacturing were included as part of the chain of commerce, the power of the Congress would be infinite: “[t]he result would be that Congress would be invested, to the exclusion of the States, with the power to regulate not only manufactures, but also agriculture, horticulture, stock raising, domestic fisheries, mining -- in short, every branch of human industry.” In a clairvoyant statement of the future of the Commerce Clause, Fuller cites as an example of the potential reach of the Commerce Clause: “Does not the wheat grower of the Northwest or the cotton planter of the South, plant, cultivate, and harvest his crop with an eye on the prices at Liverpool, New York, and Chicago?” Knowing the issue in Wickard v. Filburn and expansion of congressional Commerce Clause power ushered in by that decision, one must admire the prescience of Fuller’s opinion.

All quotes are from United States vs. E.C. Knight 156 U.S. 1 (1895).

The Lottery Case: The Commerce Clause and Federal Police Power

Champion v. Ames

188 U.S. 321 (1903)

QUICK SUMMARY: John Marshall Harlan, writing for a slim 5 to 4 majority, declares constitutional an act making it illegal to deliver lottery tickets in interstate commerce.

THE FEDERAL LOTTERY ACT: In 1895 Congress passed “'An Act for the Suppression of Lottery Traffic through National and Interstate Commerce and the Postal Service.”

“That any person who shall cause to be brought within the United States from abroad, for the purpose of disposing of the same, or deposited in or carried by the mails of the United States, or carried from one state to another in the United States, any paper, certificate, or instrument purporting to be or represent a ticket, chance, share, or interest in or dependent upon the event of a lottery, so called gift concert, or similar enterprise, offering prizes dependent upon lot or chance…[or the advertising of same] shall be punishable [for] the first offense by imprisonment for not more than two years, or by a fine of not more than $1, 000, or both, and in the second and after offenses by such imprisonment only.”

According to an editorial in the New York Times from 24 February 1903, lottery tickets were banned from being mailed since 1890. However, “the lotteries had recourse to the transportation companies as a means of carriage.” So, to circumvent anti-lottery laws, lottery tickets would be transmitted in the Federal Express equivalent of the late nineteenth century. So, the language “carried from one state to another” was added to close this loophole.

THE FACTS: Sometime around February 1, 1899, C.F. Champion (a/k/a W.W. Ogden and W.F. Champion) and Charles B. Park used the Wells-Fargo Express Company to send lottery tickets from Dallas, Texas to Fresno, California for the Pan-American Lottery Company drawing which took place monthly in Asuncion, Paraguay. The amount of the prize was $32,000.00 and tickets were sold for as much as $2.00 for a full ticket and 25 cents for an eighth of a ticket. Wells-Fargo Express Company was “a company engaged in carrying freight and packages from station to station along and over lines of railway.”

THE EVOLVING COMMERCE CLAUSE: During Justice Harlan’s dissertation on the history of the commerce clause, Justice Harlan cites Pensacola Telegraph Co. v. Western U. Telegraph Co. 96 U.S. 1 1877, an opinion by Chief Justice Waite, to explain how the commerce clause, (like commerce itself), has evolved and expanded to encompass each era’s own definition of commerce: “The powers thus granted are not confined to the instrumentalities of commerce or the postal service known or in use when the Constitution was adopted, but they keep pace with the progress of the country, and adapt themselves to the new developments of time and circumstances. They extend from the horse with its rider to the stage coach, from the sailing vessel to the steamboat, from the coach and the steamboat to the railroad, and from the railroad to the telegraph, as these new agencies are successively brought into use to meet the demands of increasing population and wealth.”

In this earlier opinion, Waite reflects on the importance of the telegraph, the matter regulated in the Pensacola case, to make an important observation that speaks to us today: “The electric telegraph marks an epoch in the progress of time. In a little more than a quarter of a century it has changed the habits of business, and become one of the necessities of commerce.” Clearly the same could be said today about the internet, e-mail and e-commerce.

Waite makes a Living Constitution argument—he looked at the founder’s intent as to the extent of the legislative power under the Commerce Clause in 1787 and concludes that it would be within the spirit of that intent for the Congress to have power to regulate telegraphs under said clause.

SUMMARY ON NINETEENTH CENTURY COMMERCE CLAUSE CASES: Analyzing a dozen or so Commerce Clause cases since Gibbons, Justice Harlan establishes four conclusions:

1. “[C]ommerce among the states embraces navigation, intercourse, communication, traffic, the transit of persons, and the transmission of messages by telegraph.

2. “[T]he power to regulate commerce among the several states is vested in Congress as absolutely as it would be in a single government.

3. “[S]uch power is plenary, complete in itself, and may be exerted by Congress to its utmost extent, subject only to such limitations as the Constitution imposes upon the exercise of the powers granted by it.”

4. “[I]n determining the character of the regulations to be adopted Congress has a large discretion which is not to be controlled by the courts, simply because, in their opinion, such regulations may not be the best or most effective that could be employed.”

ARE LOTTERY TICKETS COMMERCE?: The defendant argued that lottery tickets, having “no real or substantial value in themselves, were not properly the subjects of commerce. Justice Harlan dismissed this argument, holding tickets were bought and sold (“subjects of traffic”) and entitled the owner to a potential prize. Lottery tickets are given a value by “those who chose to sell or buy” them and, therefore, properly defined as items in commerce.

“PUBLIC MORALS” LEGISLATION: A De FACTO FEDERAL POLICE POWER: Harlan concludes, the power of the federal government to ban lotteries “for the protection of the public morals” is the equivalent of the same right in each state to legislate to protect the general welfare of its citizens—sometimes called the states’ police power: “As a state may, for the purpose of guarding the morals of its own people, forbid all sales of lottery tickets within its limits, so Congress, for the purpose of guarding the people of the United States against the 'widespread pestilence of lotteries' and to protect the commerce which concerns all the states, may prohibit the carrying of lottery tickets from one state to another.”

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: Harlan (5 to 4 decision) establishes the federal police power—the power to regulate items in interstate commerce for the general welfare of the nation. And so, the evil "pestilence of lotteries" did not pervert and corrupt clean-cut red-blooded Americans until the twentieth century when Lotto, Power Ball and Mega-Millions turned us into a nation of deviant lottery-junkies!

All quotes are from Champion vs. Ames 188 U.S. 321 (1903).

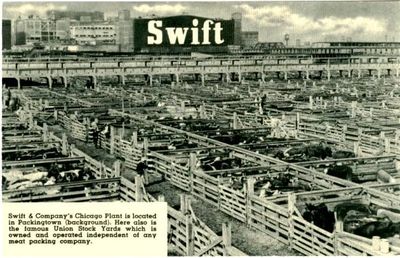

Swift and Company v. US: The Stream of Commerce Argument

196 U.S. 375 (1905)

QUICK SUMMARY: Justice Holmes broadly allows Congress to regulate anything in the “current of commerce” whether or not the part of the transaction regulated is actually in commerce.

THE FACTS: Defendants are a group of companies that control 60% of the livestock industry in the U.S. They buy and slaughter livestock and convert it into beef for consumption, which they in turn sell throughout the U.S. These companies formed a monopoly, or combination, and engaged in anti-competitive practices, to injure the business of competitors, suppliers, and ultimately increase expenses for customers. An injunction was sought under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to stop the combination from engaging in these “illegal” practices.

THE CURRENT OF COMMERCE ARGUMENT: The defendants argued that the law was attempting to regulate non-commercial matters. This was similar to the argument in E.C. Knight where the court would not allow the regulation of manufacturing. Justice Holmes concluded “commerce among the states is not a technical legal conception, but a practical one.” Although some of the elements regulated were not commerce, they were all a part of the same commercial process:

“When cattle are sent for sale from a place in one State, with the expectation that they will end their transit, after purchase, in another, and when, in effect, they do so, with only the interruption necessary to find a purchaser at the stockyards, and when this is a typical, constantly recurring course, the current thus existing is a current of commerce among the States, and the purchase of the cattle is a part and incident of such commerce.”

Thus, Holmes introduces the “current of commerce” argument, sometimes called the stream of commerce argument. The various steps may have taken place intrastate (wholly within one state), but they were all part of a current of commerce that took place in numerous steps and, ultimately, in interstate commerce

WHAT WERE THE ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRACTICES? As an aside, the way in which the titans of the beef industry unlawfully competed with the smaller companies is summarized in the case. It is a good explanation of the many unlawful practices engaged in by trusts or monopolies in this era:

“ [A] dominant proportion of the dealers in fresh meat throughout the United States [colluded] not to bid against each other in the livestock markets of the different States, to bid up prices for a few days in order to induce the cattle men to send their stock to the stockyards, to fix prices at which they will sell, and to that end to restrict shipments of meat when necessary, to establish a uniform rule of credit to dealers and to keep a blacklist, to make uniform and improper charges for cartage, and finally, to get less than lawful rates from the railroads to the exclusion of competitors.”

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: A significant (9 to 0) decision which “abandoned the restrictive interpretations of its earliest antitrust holdings and accepted a broader definition of the federal commerce power.” The “current of commerce” argument was a powerful extension of the Commerce Clause, but not sufficiently used at the time. As has been identified by Constitutional law scholars: “The ‘stream of commerce’ doctrine remained an untapped resource until the 1930s, when the New Deal Court restored expansive readings of the commerce clause power.”

All quotes are from Swift and Company v. U.S. 196 U.S. 375 (1905). Additional quotes from The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decision, Kermit L. Hall, ed., Oxford University Press, 1999, (pp. 298-299).

The Shreveport Rate Case : Intertwined Intrastate and Interstate Commerce

Houston. East & West Texas Railway Co v. US

34 U.S. 243 (1914)

THE FACTS: Rates charged by carriers for transport between Shreveport, Louisiana (westward) to cities in Texas were much greater than rates charged for transport between Dallas and Houston and the same cities (eastward) in Texas. These disparate charges, on the lines of the Houston, East & West Texas and Houston & Shreveport Companies would be charged even where the distances traveled from Shreveport were shorter than the distance traveled from Houston and Dallas. The difference in rates was “substantial and injuriously affected the commerce of Shreveport.” In short, based on the disparate rates the Texas carriers “unjustly discriminated in favor of traffic within the state of Texas.” The Railroad Commission of Louisiana brought suit in the commerce court of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) whose authority to regulate intrastate rates (wholly within Texas) was challenged.

“PARAMOUNT CHARACTER” OF THE COMMERCE CLAUSE: Justice Charles Evans Hughes (back in the simple days before he was chief justice) writes in his majority opinion of the “paramount character of the power confided to Congress to regulate commerce among the several states.” He concludes, if Congress has the power, it “dominates” in that field. By looking to the original intent of the founding fathers, he explains the necessity for this federal supremacy: “The purpose was to make impossible the recurrence of the evils which had overwhelmed the Confederation, and to provide the necessary basis of national unity by insuring 'uniformity of regulation against conflicting and discriminating state legislation.'”

WHERE INTRASTATE AND INTERSTATE ACTIVITY IS INTERTWINED: Sometimes activity which takes place wholly within one state (intrastate) cannot be separated from the interstate activity. When that happens, the federal government has the power to regulate both the intrastate and interstate components of the activity: “Wherever the interstate and intrastate transactions of carriers are so related that the government of the one involves the control of the other, it is Congress, and not the state, that is entitled to prescribe the final and dominant rule, for otherwise Congress would be denied the exercise of its constitutional authority, and the state, and not the nation, would be supreme within the national field.” The only question that remained, according to Justice Hughes, was whether the attempted regulation was proper. To Hughes, it was: “We find no reason to doubt that Congress is entitled to keep the highways of interstate communication open to interstate traffic upon fair and equal terms. *** The use of the instrument of interstate commerce in a discriminatory manner so as to inflict injury upon that commerce, or some part thereof, furnishes abundant ground for Federal intervention.” The fact that the discriminatory rates affected intrastate as opposed to interstate regulation was deemed “immaterial.”

WHAT WAS THE INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION? Created by the Interstate Commerce Act, passed in 1887, the Interstate Commerce Commission regulated America’s railroad industry. The ICC, the first regulatory agency in America, consisted of a five member board, prevented monopolies from being formed by the largest few railroads, and fought discriminatory rate charging practices, such as special (discount) rates which railroads would charge for other captains of industry. Although regulation proved difficult early on, the power of the ICC was greatly enhanced by passage of the Hepburn Act of 1906 and Mann-Elkins Act in 1910 which further defined the ICC’s regulatory power and shifted the burden of proof as to the reasonableness of rates charged onto the railroads. The ICC’s power continued to grow, and eventually included regulating eight-hour work days for railroad employees, and culminated in government takeover of the railroads from 1918 to 1920.

For more information see Interstate Commerce Act – American Experience: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/streamliners-commerce/

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: The ICC was a forerunner to the plethora of New Deal agencies that followed. Thus, the decision (7 to 2) set a strong precedent for the Supreme Court’s expansive approach to the Commerce Clause from the late 1930s and beyond.

All quotes are from Houston, East & West Texas Railway Co. v. U.S. 234 U.S. 243 (1914).

Early Social Welfare Legislation vs. Laissez Faire: Hammer v. Dagenhart

247 U.S. 251(1918)

THE KEATING-OWEN ACT of 1916: Enacted September 1, 1916, the act attempted to fight the exploitive practice of hiring child labor in the United States through the power of the Commerce Clause. The act “prohibit[ed] transportation in interstate commerce of goods made at a factory in which, within thirty days prior to their removal therefrom, children under the age of 14 years have been employed or permitted to work, or children between the ages of 14 and 16 years have been employed or permitted to work more than eight hours in any day, or more than six days in any week, or after the hour of 7 P.M. or before the hour of 6 A.M.

THE FACTS: Roland Dagenhart, the father of two minor sons (one under age 14 and one under age 16) worked with his sons in a cotton mill in Charlotte, North Carolina. He challenged the constitutionality of the Keating-Owen Act of 1916 which denied his children the freedom to work.

PRIOR INSTANCES OF COMMERCE CLAUSE REGULATION: From his reading of Gibbons, Justice William Day concluded the Commerce Clause power “is one to control the means by which commerce is carried on” and not to “forbid” certain types of commerce “and thus destroy it as to particular commodities.” To Justice Day, when congress regulates “commodities” it does so “[based] upon the character of the particular subjects dealt with.” He cited as examples Champion v Ames which allowed a law that banned lottery tickets, Hipolite Egg Co. v. U.S. which held the Pure Food and Drug Act constitutional and Hoke v. U.S. which deemed the White Slave Traffic Act” banning the transportation of women for prostitution. The “exceptional power exerted” under the Commerce Clause in these instances was based on “the exceptional nature of the subject here regulated.” (Citing Clark Distilling Co. v. Western Maryland Railway Co. 242 U.C. 311 which regulated the transportation of liquor.) Since the transportation of the items was the evil attempting to be curbed, “interstate transportation was necessary to the accomplishment of the harmful results.” However, with child labor, transportation of the goods had nothing to do with the evil.

MANUFACTURING AND MINING ARE NOT COMMERCE: Reverting to the E.C. Knight rationale, Justice Day concluded: “The making of goods and the mining of coal are not commerce, nor does the fact that these things are to be afterwards shipped, or used in interstate commerce, make their production a part thereof.” By concluding as such, Day utterly ignored the “current of commerce” theory of Justice Holmes in Swift. In Day’s view, the Commerce Clause gave Congress power over commerce, alone, “not to give it authority to control the States in their exercise of the police power over local trade and manufacture.”

HOLMES’ DISSENT: Justice Day’s slim 5 to 4 decision had a strong dissent from the Great Dissenter himself, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. In it he points out the departure the majority opinion takes from a line of Supreme Court opinions empowering Congress through the Commerce Clause. He also points out the logical flaws with the opinion.

Holmes disputes the regulation-of-evils-only argument by criticizing the court for using its view of morality to identify what is or is not evil, since that is not the job of a court:

“The notion that prohibition is any less prohibition when applied to things now thought evil I do not understand. But if there is any matter upon which civilized countries have agreed -- far more unanimously than they have with regard to intoxicants and some other matters over which this country is now emotionally aroused--it is the evil of premature and excessive child labor. I should have thought that, if we were to introduce our own moral conceptions where in my opinion they do not belong, this was preeminently a case for upholding the exercise of all its powers by the United States.”

It is in the exclusive power of Congress to determine whether it is proper purpose for a power to be exercised: “the propriety of the exercise of a power admitted to exist in some cases was for the consideration of Congress alone, and that this Court always had disavowed the right to intrude its judgment upon questions of policy or morals.”

Finally, Holmes gives an excellent explanation of federalism—one that looks to the future of congressional law in the twentieth century and beyond: “The act does not meddle with anything belonging to the States. They may regulate their internal affairs and their domestic commerce as they like. But when they seek to send their products across the state line, they are no longer within their rights. If there were no Constitution and no Congress, their power to cross the line would depend upon their neighbors. Under the Constitution, such commerce belongs not to the States, but to Congress to regulate. It may carry out its views of public policy whatever indirect effect they may have upon the activities of the States. Instead of being encountered by a prohibitive tariff at her boundaries, the State encounters the public policy of the United States, which it is for Congress to express. The public policy of the United States is shaped with a view to the benefit of the nation as a whole….The national welfare, as understood by Congress, may require a different attitude within its sphere from that of some self-seeking State. It seems to me entirely constitutional for Congress to enforce its understanding by all the means at its command.”

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: Laissez Faire is alive and well in this era of Lochner. However, Holmes’ famous dissent certainly predicts the future.

All quotes are from Hammer v. Dagenhart 247 U.S. 251 (1918).

The Commerce Clause and the New Deal: 1936-1942

Overview: The Death of Federalism

In a series of cases from 1936 to 1942, the Commerce Clause transformed into the all-empowering grant of power that we know today. During those years, a seismic shift took place in the Supreme Court's jurisprudence with respect to economic regulations, federalism and the power of Congress. From the last gasps of federalism in Carter v. Carter Coal Co. to the seemingly limitless substantial effects test in Wickard v. Filburn, the Commerce Clause reached its full potential—perhaps beyond the founders wildest dreams. ..or nightmares.

Federalism's Last Hurrah: A.L.A. Schecter Poultry v. US

295 U.S. 495 (1935)

THE NATIONAL INDUSTRIAL RECOVERY ACT: Among the multitude of alphabet nick-named administrative agencies passed under FDR’s New Deal program to combat the Great Depression , the centerpiece was the National Industrial Recovery Act. Drafted, in the words of FDR himself, to “put people back to work” the NIRA did three things. First, it created the Public Works Administration, to fund large public projects, and put the unemployed back to work in the immediate future. Second, it created the National Recovery Administration which would encourage businesses in a variety of industries to get together and establish fair competitive practices, on a voluntary basis. Production and prices would be controlled, and anti-trust laws would be suspended. Finally, the NIRA authorized President Roosevelt to enact administrative codes regulating various industries, promulgating maximum hours, minimum wages, banning unfair competition practices and providing for inspection of products. Eventually, 557 codes were implemented by the Roosevelt administration—one was called the “Live Poultry Code” which regulated the national poultry industry

From David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, pp. 150-151. From Amity Shales, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, pp. 150-151

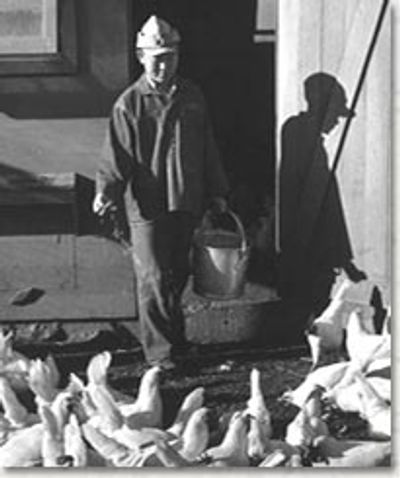

FACTS: Joseph Schechter and his brothers operated the Schechter Live Poultry Market in Brooklyn, New York. They purchased live poultry from the West Washington Market in New York City from intermediaries ("commission men") and occasionally from intermediaries in Philadelphia. The poultry was "trucked" to their slaughterhouses in Brooklyn and "sold usually within twenty-four hours, to retail poultry dealers and butchers who sell directly to consumers." Before sale, the poultry was slaughtered by "schochtim" ("slaughterers") employed by Schechter. Importantly, (to the justices, at least); "[d]efendants do not sell poultry in interstate commerce.”

The Schechters ran a-fowl (hahahahaha) of the Live Poultry Code by not following "the minimum wage and maximum hour provisions of the Code." Additionally, the Schecters did not comply with Code inspections, falsified records, did not maintain reports and sold to dealers without licenses. Finally, they did not follow the requirement of "straight killing" or as Justice Hughes identified it, "straight selling." To improve efficiency, the Code required poultry sellers to sell the first chicken they grabbed in a coop; it did not allow buyers to choose the chickens they wanted to purchase. In the words of Joseph Heller, the Schechters’ attorney, during oral arguments: “His customer is not permitted to select the [chicken] he wants. He must put his hand in the coop when he buys from the slaughterhouse and take the first chicken that comes to hand.”

Additional facts from The Forgotten Man, p. 241

THE TENTH AMENDMENT vs. THE GREAT DEPRESSION: Chief Justice Hughes begins by conceding the severity of the Great Depression—“the grave national crisis with which Congress was confronted.” Although he concedes that "[e]xtraordinary times may call for extraordinary measures…[but crises] do not create or enlarge constitutional powers.” The Tenth Amendment, which reserves all powers not “delegated” to the federal government “to the states, respectively, or the people” was drafted and passed to prevent Congress from exercising “extraconstitutional authority.” In practice, the codes promulgated by the NIRA were not simply voluntary but a “coercive exercise of the lawmaking power.”

THE DELEGATION ISSUE: The NIRA authorizes the president to pass various codes regulating numerous industries—a power akin to making laws. To the Court, this was a separation of powers violation that doomed the statute: “the code-making power authority conferred is an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power.”

INTRASTATE COMMERCE THAT HAS COME TO A “PERMANENT REST: According to Chief Justice Hughes, the Live Poultry Code improperly regulated matters taking place entirely within one state (intrastate). Once the poultry arrived at the slaughterhouse in Brooklyn, “interstate transactions in relation to that poultry then ended.” Thereby, the “slaughtering” and “sales” by the Schechters were not “transactions in interstate commerce” and could not be regulated. Dismissing the “current of commerce” argument of Justice Holmes, Hughes concludes “[t]he poultry had come to a permanent rest within the State” and the “flow in interstate commerce has ceased.”

DIRECT vs. INDIRECT AFFECTS TEST: Hughes returns to this analysis which dates back to E.C. Knight, that allows regulation of only those matters that have a “direct effect” on interstate commerce. In identifying whether something has a direct or indirect effect, “[t]he precise line can be drawn only as individual cases arise.” While the distinction itself is imprecise, the necessity for it is laid out convincingly by Chief Justice Hughes:

“If the commerce clause were construed to reach all enterprise and transactions which could be said to have an indirect effect upon interstate commerce, the federal authority would embrace practically all the activities of the people.” Without the direct vs. indirect distinction, “there would be virtually no limit to the federal power and, for all practical purposes, we should have a completely centralized government.” Hughes does not attempt to evaluate the “economic advantages and disadvantages of such a centralized system” but concludes “the Federal Constitution does not provide for it.”

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: Declaring the hours and wages of employees and the methods for selecting chicken a local matter with, at most, an indirect effect on commerce, the Code was held to be invalid. The unanimous decision by the Supreme Court was one of the controversial anti-New Deal decisions which set off, along with Roosevelt’s subsequent landslide victory in the 1936 election, the Court Packing Scheme.

All quotes are from A.L.A. Schecter Poultry Corp. v. U.S. 295 U.S. 495 (1935).

Federalism Hanging on by a Thread: Carter v. Carter Coal Co.

298 U.S. 238 (1936)

FACTS: The “Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935” was passed for the purpose of regulating the national coal industry. The Act created a national coal commission, separated the country into various coal districts run by local boards and fixed prices, wages, hours and improved working conditions of miners. The statutory scheme imposed a 15% excise tax on the sale of coal by coal companies throughout the country, but allowed a 13½ “draw-back” or refund to those companies in the industry who voluntarily followed the regulations imposed by the Act. James W. Carter, a shareholder in the company, was against cooperating with the act. The board voted against him, fearing payment of the full tax without the “draw-back” would bankrupt the company. Mr. Carter, a stockholder in the company, brought suit to enjoin his company from complying with the tax because the Act was unconstitutional.

GOVERNMENT OF ENUMERATED POWERS- THE TENTH AMENDMENT: Referencing the Tenth Amendment as the protection implemented by the founders to assure a future Congress did not attempt to legislate for the general welfare (as the Congress seemed to be doing under the current Act), Justice George Sutherland explained “this is a government of enumerated powers.” Since the states pre-dated the federal government, their legislative powers, similarly, “antedated” the power of the federal government. The Tenth Amendment ("which was seemingly adopted with prescience of just such contention as the present") assured that the federal government shall not "attempt to exercise powers which had not been granted" in Article 1 Section 8 of the Constitution. Expansion of the enumerated powers "should only be granted by the people" through the Article V Amendment process.

FEDERALISM: SUPERIORITY OF STATE POWERS WHERE STATES ARE SOVEREIGN: The old guard’s approach to federalism is encapsulated in a few paragraphs by Justice Sutherland: “Those who framed and those who adopted [the Constitution] meant to carve from the general mass of legislative powers, then possessed by the states, only such portions as it was thought wise to confer upon the federal government.

“The national powers of legislation were not aggregated but enumerated…with the result that what was not embraced by the enumeration remained vested in the states without change or impairment. *** [The federal government] possesses no inherent power in respect of the internal affairs of the states. *** The determination of the Framers Convention and the ratifying conventions to preserve complete and unimpaired state self-government in all matters not committed to the general government is one of the plainest facts which emerges from the history of their deliberations.”

FEDERALISM’S LAST HURRAH: In one of the last opinions respecting the strong walls of federalism, a voice from the past—from the fading and foggy federalism of yesteryear—attempts to balance the economic independence of the states, while respecting the power of the federal government. This philosophy would soon be left only in dusty casebooks in slowly obscuring locations in law libraries. However, Sutherland’s eloquent essay on federalism still speaks to the American people—those who are still listening—when they lament the omnipotence of the federal government.

“Every journey to a forbidden end begins with the first step; and the danger of such a step by the federal government in the direction of taking over the powers of the states is that the end of the journey may find the states so despoiled of their powers, or--what may amount to the same thing--so relieved of the responsibilities which possession of the powers necessarily enjoins, as to reduce them to little more than geographical subdivisions of the national domain. It is safe to say that if, when the Constitution was under consideration, it had been thought that any such danger lurked behind its plain words, it would never have been ratified.”

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF BENEFICIAL LAWS: The Constitution, being the supreme law of the land, is supreme to Congressional laws, dating back to Marbury v. Madison. And, in Sutherland’s best John Marshal impersonation, he explains why it is his judicial duty to invalidate unconstitutional laws, even good ones:

“[S]upremacy of a statute enacted by Congress is not absolute but conditioned upon its being made in pursuance of the Constitution. And a judicial tribunal, clothed by that instrument with complete judicial power, and, therefore, by the very nature of the power, required to ascertain and apply the law to the facts in every case or proceeding properly brought for adjudication, must apply the supreme law and reject the inferior statute whenever the two conflict. In the discharge of that duty, the opinion of the lawmakers that a statute passed by them is valid must be given great weight; but their opinion, or the court's opinion, that the statute will prove greatly or generally beneficial is wholly irrelevant to the inquiry.”

MANUFACTURING IS NOT COMMERCE: With Sutherland’s grand statements about American Constitutional government and federalism behind him he gets down to the nuts and bolts of his Commerce Clause analysis. In a throwback to E.C. Knight Sutherland remembers the old distinction, that what takes place wholly within one state PRIOR to being in commerce is NOT commerce despite any intent or subsequent transport in interstate commerce. He concludes, simply, manufacturing is not commerce; the production or manufacture of goods “within a state” which are intended to be sold or transported outside the state does not render their production of manufacture subject to federal regulation under the commerce clause.”

It’s the flip side of Schecther—the federal government cannot constitutionally regulate activity not yet in interstate commerce (Carter) nor can it regulate activity that has come to rest in its final destination post- interstate commerce (Schecther).

LAST DAYS OF INDIRECT vs. DIRECT: THE LOCAL EVILS TEST: Referencing and expanding upon Schechter, Sutherland attempts to flesh out this fuzzy and subjective test. To explain a direct effect, Sutherland explains the activity must not have “an efficient intervening…condition” between the activity and the interstate commerce. The focus with direct vs. indirect, according to Sutherland, is not on “the magnitude” of the activity but on “the manner” of the activity. So, if someone produces “a single ton of cool intended for interstate commerce…the effect does not become direct by multiplying the tonnage.” As much as Congress wants to put an end to “the evils which come from the struggle between employers and employees…[these] are local evils over which the federal government has no legislative control.”

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: The few excerpts from the case, particularly the oft-quoted and evocative “journey to a forbidden end” are the old-guard’s warning to future generations of the danger of an America without federalism. Carter represents the last stand of the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse. For better or worse, within one year, Commerce Clause jurisprudence would never be the same.

All quotes are from Carter v. Carter Coal Co. 298 U.S. 238 (1936).

Federalism and the Substantial Affects Test: NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp.

301 U.S. 1 (1937)

THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT: Passed in July 1935, and also known as the Wagner Act for its sponsor, New York Senator Robert R. Wagner, this pro-union law protected workers’ rights to organize. Its mission, as stated in the preamble to the Act was “to protect the rights of employees and employers, to encourage collective bargaining, and to curtail certain private sector labor and management practices, which can harm the general welfare of workers, businesses and the U.S. economy.” The NLRA covered employers in all industries in interstate commerce, except airlines, railroads, agriculture and government. The National Labor Relations Board (created under the Act) was authorized to arbitrate labor-management disputes, guarantee fair union elections, and penalize employers engaging in unfair labor practices. The NLRA “sets forth the right of employees to self-organization and to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing.” The Act, one of the strongest pro-union statements by the Congress, “contributed to a dramatic surge in union membership and made labor a force to be reckoned with both politically and economically.”

For more information (and for the source of the quote) see the National Labor Relations Act at www.ourdocuments.gov http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=67

FACTS: The Beaver Valley Lodge, an affiliate of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers of America, a labor organization, brought a proceeding under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 against Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation alleging unfair labor practices. Specifically, the union alleged the Corporation coerced, intimidated and discharged persons trying to unionize. The NLRB ordered Jones and Laughlin to cease and desist from these practices and reinstate ten employees, but the corporation refused to comply. The NLRB attempted to enforce its order in the Circuit Court of Appeals, but the court denied the petition, holding “the order lay beyond the range of federal power.”

ACTS BURDENING OR OBSTRUCTING INTERSTATE COMMERCE: Chief Justice Hughes identifies the purpose of the Act, as laid out by Congress: “[The Act] purports to reach only what may be deemed to burden or obstruct [foreign or interstate] commerce.” It seems, Hughes is taking Congress’ stated intent at face value. He identifies a “familiar principal that acts which directly burden or obstruct interstate or foreign commerce, or its free flow, are within the reach of the congressional power.” The inquiry to Hughes is “the effect upon commerce, not the source of the injury.” The question “[w]hether or not particular action does affect commerce in such a close and intimate fashion as to be subject to federal control” was to be determined on a case by case basis. Congress on passing the NLRA simply intended to "safeguard the right of employees to self-representation and to select representatives of their own choosing for collective bargaining." According to Hughes, this is a "fundamental right...proper[ly] subject for condemnation by competent legislative authority.”

THE SUBSTANTIAL RELATIONS TEST: Having established that the activity was one the Congress could properly regulate, it remained for Hughes to establish the Commerce Clause as the proper enabling authority. To do so, Hughes looks to whether there is a "substantial relation" between the inter- and intra- state commerce. He establishes the new test for Commerce Clause analysis as he explains: "although activities may be intrastate in character when separately considered, if they have such a close and substantial relation to interstate commerce that their control is essential or appropriate to protect that commerce from burdens and obstructions, Congress cannot be denied the power to exercise that control." In order to preserve “our dual system of government" and not destroy "the distinction between what is national and what is local" Hughes allows congress to regulate any activity that “threatens to obstruct or unduly burden the freedom of interstate commerce.” Referencing the Shreveport Rate Case, he identifies the intrastate activities of “carriers” (i.e. railroads) as something that Congress can properly regulate. So, in Shreveport, the “local activity” of rates wholly within a state could be regulated by Congress properly because “they bear such a close relation to interstate rates that effective control of the one must embrace some control over the other.” It did not matter that the employees here were “engaged in production” which had been considered a local activity in past decisions. The question is one of the effect on interstate commerce of aspects of that production. To tie in his decision with current Commerce Clause jurisprudence, Hughes, with little explanation distinguished both Schechter, finding the effects there “remote” and Carter because of the “improper delegation of legislative power.”

REJECTION OF DIRECT vs. INDIRECT TEST: Hughes abandons the old direct vs. indirect test, for its failure to acknowledge the potentially “catastrophic” effect of work stoppages in localities across the country. Congress, thus, must be allowed to pass laws that “protect interstate commerce from the paralyzing consequences of industrial war.” In short, labor relations at Jones and Laughlin clearly depict “the close and intimate relation which a manufacturing industry may have to interstate commerce.” Thus, the NLRB acted properly, and the National Labor Relations Act was a valid exercise of the Commerce Clause power of Congress.

McREYNOLDS’ DISSENT: Joined by the other three members of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—Justices Van Devanter, Sutherland and Butler—McReynolds carried the vanishing flag of federalism in his dissent to this five to four opinion. Calling the “far-reaching” majority opinion “a departure from what we understand has been consistently ruled here” in Kidd v. Pearson, Carter and Schechter, and labeling the powers of the three person Board “extraordinary,” McReynolds argues, “that view of congressional power would extend it into almost every field of human industry.” To the four horsemen, the effect of discharging ten employees on interstate commerce was “indirect and remote in the highest degree.” McReynolds prophetically predicts that if Congress can act in this way based on the Commerce Clause, “[a]lmost anything--marriage, birth, death--may in some fashion affect commerce” and be proper grounds for Congressional regulation. “It seems clear to us that Congress has transcended the powers granted.” That flag of federalism unfurled by McReynolds, would soon be in mothballs.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: The new majority (established with the alleged “switch in time” of West Coast Hotel v. Parrish) establishes the substantial effects test—one which will allow Congress broad powers, remove the Supreme Court from evaluating economic regulations and see the Commerce Clause enable Congress to act however it sees fit for the next 50 years, and beyond.

All quotes are from N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. 301 U.S. 1 (1937).

The Substantial Affects Test Part II: US v. Darby

312 U.S. 100 (1940)

THE FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT: Signed into law on June 25, 1938, after Congress had adjourned, the FLSA banned child labor, set a minimum hourly wage of .25 cents an hour and a maximum work week of 44 hours. The enabling power was the Commerce Clause. As the case itself explains: “[The FLSA] set up a comprehensive legislative scheme for preventing the shipment in interstate commerce of certain products and commodities in the United States under labor conditions as respects wages and hours which fail to conform to standards set by the Act.” So, if products are manufactured by companies that did not comply with the FLSA (as to wages, hours and child labor) Congress could penalize them under the Commerce Clause.

As legend has it, once FDR emerged victorious from his attempts to pack the court (the court-packing scheme being unnecessary after Justice Roberts’ switch in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish) he asked his Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins “What happened to that nice unconstitutional bill you tucked away?” The draft bill was worked on by Thomas Corcoran and Benjamin Cohen, two of FDR’s legal advisers and brain trusters, strengthened with a prohibition on child labor (under 16) and introduced by the president in spring 1937 proclaiming America must give “all our able-bodied working men and women a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.” A contentious yearlong battle ensued and after re-writes and much politicking, the FLSA became law. The act is considered the “last major piece of New Deal legislation.”

From The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions, Kermit L. Hall ed., 1999, p. 70. Historical material from the U.S. Department of Labor website article Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage, by Jonathon Grossman. http://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/flsa1938.htm

FACTS: The Darby Lumber Company was “engaged, in the State of Georgia, in the business of acquiring raw materials” a/k/a trees, and converting them into finished lumber which was then shipped in interstate commerce. The company did not pay employees the minimum wage required under the FLSA and employed them for hours in excess of the maximum hours under the Act, without paying overtime. They were brought up on a series of counts in violation of the Act; Darby challenged the constitutionality of the Act.

RETURN TO THE FEDERAL POLICE POWER: Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, writing for a unanimous (8 to 0) court, began by acknowledging “the power of Congress to prohibit transportation in interstate commerce of noxious articles.” He cites as precedent the Champion v. Ames(the Lottery Case), Hipolite Egg Co. v. US, and Hoke v. US which banned, respectively lottery tickets, improperly labeled eggs (regulated under the Pure Food and Drug Act), and women transported for illicit purposes (regulated under the Mann Act). The premise of those cases is that Congress can regulate and exclude from interstate commerce any articles it deems “injurious to the public health, morals or welfare.” This is a police power that the states enjoy and, as was identified in the Lottery Case, it is the equivalent in Congress...a sort of Federal Police Power. However, the items regulated need not be harmful, as Hammer v. Dagenhart held. The requirement that Congress can only regulate “harmful or deleterious” items enunciated by Hammer “was novel when made and unsupported by any provision of the Constitution, [it] has long since been abandoned.”

SUBSTANTIAL EFFECTS TEST: Continuing along with the NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin rationale, Stone allowed Congress to regulate activities, even wholly intrastate activities, provided they had “a substantial effect” on commerce. Citing precedent, Stone concludes, Congress may “require inspection and preventive treatment of all cattle” and mandate inspections of tobacco, even if only a portion of the items will travel in interstate commerce. Again, the strongest precedent, like in Jones and Laughlin, was the Shreveport Rate Case where intrastate railway rates could be regulated based on their effect on interstate commerce.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CASE: By the time the Darby decision is handed down, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are merely a historical footnote to the history of the court. Justice Willis Van Devanter retired in 1937 and was replaced by Justice Hugo Black (FDR appointee). Justice George Sutherland retired in 1938, and was replaced by Justice Stanley Reed (FDR appointee). Justice Pierce Butler died in 1939 while still on the court. His vacated seat was filled by Justice Frank Murphy (FDR appointee). The last horseman, Justice James McReynolds, retired in 1941 and was replaced by Justice James Byrnes. McReynolds recused himself from the decision, hence the unanimity. The transformation of the Commerce Clause into an omnipotent superpower was complete.

All quotes are from U.S. v. Darby 312 U.S. 100 (1940).

Commerce Clause Gone Wild!: Wickard v. Filburn, the Aggregation Theory

THE AGRICULTURAL ADJUSTMENT ACT: On May 13, 1933, FDR signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act into law (AAA). Drafted by Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, brain truster (and agricultural economist) Rexford Tugwell, one of the central aspects of the AAA was “planned scarcity,” whereby farmers were encouraged to produce less through various methods, including direct payments to farmers who did not grow crops (benefit payments), loans to those who stored crops and destruction of crops and livestock. (This last, and most controversial step was only done in 1933 and only to cotton crops and pigs because the Act was not passed before the season began). To quote President Roosevelt, from a speech to farmers in 1935:

“[The AAA enacted] a plan for the adjustment of totals in our major crops, so that from year to year production and consumption would be kept in reasonable balance with each other, to the end that reasonable prices would be paid to farmers for their crops and unwieldy surpluses would not depress our markets and upset the balance.”

From FDR's Address on Agricultural Adjustment Act, May 14, 1935 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/fdr-aaa/

Simply, taxes and penalties collected by the AAA would raise money that would be used to pay subsidies to farmers if they did not plant crops, or did not bring crops to market, thus artificially maintaining the price of significant crops. To quote from the Wickard opinion:

“The general scheme of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 as related to wheat is to control the volume moving in interstate and foreign commerce in order to avoid surpluses and shortages and the consequent abnormally low or high wheat prices and obstructions to commerce.”

The AAA of 1933 was declared unconstitutional in U.S. v. Butler 297 U.S. 1 (1936); the Court held the tax on the agricultural processors violated the Tenth Amendment because it attempted to regulate production, a matter controlled by the states. After the Court’s alleged “switch in time,” a new Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 was passed supposedly remedying the unconstitutional aspects of the earlier AAA. It was not so much the constitutionality of the laws that changed, as much as the philosophies of the justices. The court held in Mulford v. Smith 307 U.S. 38 (1939) that the AAA of 1938 was constitutional. To quote Professor Jim Chen, an authority on Wickard: “though the tobacco marketing quotas imposed by the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 intruded far more aggressively into the farm economy than the processing taxes inspired by the 1933 Act, Mulford approved the 1938 Act with little fanfare. Whereas the 1933 Act had been condemned merely three years earlier as an unconstitutional "plan to regulate and control agricultural production, a matter beyond the powers delegated to the federal government," (U.S. v. Butler 297 US 1, 68 (1936), Mulford blessed the 1938 Act as a program "intended to foster, protect and conserve [interstate] commerce." Mulford v. Smith, along with US v. Darby and several other decisions allowed Roosevelt to “reinvent the Commerce Clause.” Jim Chen, Filburn’s Legacy, 52 Emory Law Journal 1719 (2003).

For the historical background to the Agricultural Adjustment Act I have relied on the sources quoted above and David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, pp. 199-205.

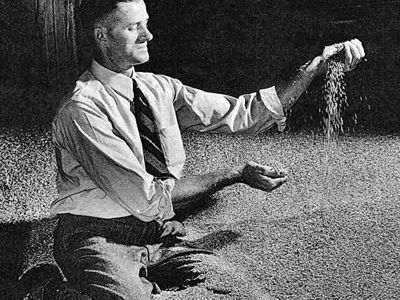

FACTS: “[Roscoe Filburn] owned and operated a small farm in Montgomery County, Ohio, maintaining a herd of dairy cattle, selling milk, raising poultry, and selling poultry and eggs. It has been his practice to raise a small acreage of winter wheat, sown in the Fall and harvested in the following July; to sell a portion of the crop; to feed part to poultry and livestock on the farm, some of which is sold; to use some in making flour for home consumption, and to keep the rest for the following seeding.” Each year, the Secretary of Agriculture would establish the “national acreage allotment” of wheat. Local committees, such as the County Agricultural Conservation Committee in Montgomery County, Ohio, would promulgate the acreage allotage for each farmer in the county. So, in the case of Mr. Filburn’s farm, the Committee gave him a “wheat acreage allotment of 11.1 acres and a normal yield of 20.1 bushels of wheat an acre.” He received two notices of his allotment but sowed 23 acres yielding 239 excess bushels of wheat which subjected him to a penalty of 49 cents per bushel or $117.11. Mr. Filburn refused to pay the penalty or store the excess with the Secretary; he was refused a “marketing card” which protects a buyer of his wheat from liability under the penalty. Mr. Filburn “sought a declaratory judgment that the wheat marketing quota provisions of the Act….were unconstitutional because not sustainable under the Commerce Clause.”

LOCAL/INDIRECT EFFECTS TESTS DISMISSED: Justice Robert Jackson, in addressing the Commerce Clause issue in the case, held U.S. v. Darby controls except that the regulation in the present case dealt with “production not intended in any part for commerce, but wholly for consumption on the farm.” After all, Mr. Filburn used the wheat to feed poultry and livestock on his farm, for use in his home and for his future seed. The Act controls the production of the wheat, whether or not said wheat was intended for sale. Filburn’s attorneys argued the old, and recently discredited, argument that production and manufacturing were local matters with only an indirect effect upon interstate commerce. These old arguments he dismissed by engaging in an overview of the Supreme Court’s Commerce Clause jurisprudence over the last century and concluded “questions of the power of Congress are not to be decided by reference to…nomenclature such as “production” and “indirect” and foreclose consideration of the actual effects of the activity in question upon interstate commerce.”

THE SUPREME COURT’S COMMERCE CLAUSE JURISPRUDENCE: Justice Jackson begins with the approach by Chief Justice Marshall in Gibbons v. Ogden which he summarizes to hold “effective restraints on [Congress’ exercise of commerce clause power] must proceed from political, rather than judicial, processes.” The Commerce Clause for one hundred years after Gibbons dealt “almost entirely with the permissibility of state activity which it was claimed discriminated against or burdened interstate commerce.” These are the dormant (or negative) Commerce Clause cases which prevented states from enacting laws burdening interstate commerce (usually to discriminate against other states and give preference for residents of their own states.) Jackson summarizes the approaches in U.S. V. E.C. Knight Co., Swift & Co. v. U.S. and the Shreveport Rate Cases to reach a realistic conclusion upon implementing Congressional power under the Commerce Clause “questions of federal power cannot be decided simply by finding the activity in question to be “production,” nor can consideration of its economic effects be foreclosed by calling them “indirect.”

THE SUBSTANTIAL EFFECTS TEST: After dismissing the ‘production,’ ‘consumption’ or ‘marketing’ distinctions for the purposes of determining whether federal power could be exercised, what test did Justice Jackson apply? Ultimately, even local activity could be regulated by Congress under the Commerce Clause power “if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce” regardless of whether that effect was defined as direct or indirect—a distinction that was no longer relevant.

THE AGGREGATION THEORY: Having dismissed all of the prior tests and distinctions (the local activity test, manufacturing/production vs. commerce distinction and the direct vs. indirect test) and replacing them with the substantial effects test, the last issue was constitutionalizing the regulation of intrastate activity—not just intrastate, but activity taking place wholly on one farm. For this, Justice Jackson argued something that has since been labeled the aggregation theory: “That [Filburn’s] own contributions to the demand for wheat may be trivial itself is not enough to remove him from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his contribution, taken together with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.” Simply, if all the farmers in America grew wheat for their own personal use then that would have a substantial effect on interstate commerce.